"Now that the Tories are back we need a government in Scotland that will fight for what really matters." The immortal opening lines of Labour's 2011 Holyrood manifesto, the logic behind this gambit always seemed a little confused. Labour, correctly, identified that the election of Conservative Government in the UK in 2010 had the natives riled, but how to rile them up against the SNP minority government in Holyrood in particular? How to transform the resource of Tory rule into a rod to smack Salmond about with?

A parallel challenge and opportunity now seems to present itself to the Yes campaign. While Labour hoped to use anti-Toryism as a way of defeating the SNP, the SNP hope to make use of the same resource to deliver Scottish independence. Accordingly, the case for independence now emanating from the SNP and indeed, from the Yes campaign, has been strikingly left-inflected in its political rhetoric, and explicitly anti-Tory in its critique of the Better Together campaign, and Labour's participation in it.

But is this a terrifically good idea? Will independence be won on the basis of the campaign that lost the Labour Party the general election in 1983, and the Holyrood election in 2011 in such style? A few salient facts. Although BBC Scotland put out a programme entitled

Why Don't Scots Vote Tory? shortly after the 2010 election, and the party can only count one MP north of the border, the narrative about Scotland's essential (and historically, relatively recent) anti-Tory politics is generally overstated. In the last general election, a polarised contest if ever there was one, David Cameron's Party attracted some 412,855 votes in Scottish constituencies, just 78,531 behind the SNP's showing that year.

More recently, in the Holyrood election of 2011, there is plenty of evidence in the breakdown of

regional votes in constituencies that the SNP has been able able to pick up substantial support from what we might think of as anti-Labour voters. In 2011, the Tories saw 15 MSPs elected, three in respect of the constituencies in the south of Scotland. If you look into the results, you find something curious.

John Scott beat his Nationalist opponent in Ayr by 1,113 votes, but the SNP romped home in the constituency's regional votes, with the SNP, coming 5,838 votes ahead of the Tories.

A similar story is told by the figures from Ettrick, Roxburgh and Berwickshire, and Galloway and West Dumfries. In both constituencies, the Tory candidate defeated a Nationalist opponent (by 5,334 and 862 votes respectively) but the SNP won comfortably on the list, ratcheting up 964 and a more decisive 3,421 more votes than the Tories apiece. Is it wise for pro-independence campaigners, by dint of their rhetoric, to write off half a million voters from the get go, many of whom are likely at some point in Holyrood's life, to have supported the SNP?

On balance, probably. We know that in order to win the referendum, we have to marshal a majority, even a bare majority, for the proposition. To govern is, classically, to choose, and so is to campaign. We needn't win the entire country, just 50.1%. The hard-headed question, is not how to persuade everyone, but how to cobble together and sustain a winning coalition across the nation. To make some arguments is inevitable to sacrifice others. To win some pockets of support is to risk losing others. So what does the evidence suggest? Why might it be a canny strategy to try to exploit anti-Tory feeling, and to attempt to connect it up with self-determination?

In July of last year, the pollster

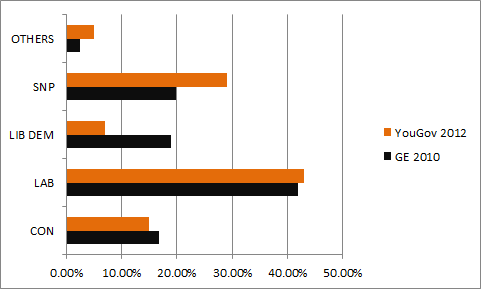

YouGov investigated Scots voters' Westminster voting intentions and attitudes towards independence. As you might expect, the significant development between 2010 and 2012 was the collapse in the Liberal Democrat vote, from just shy of 19% in 2012 to just 7% in the YouGov poll, with the SNP enjoying an upward bounce, and the Tories and Labour parties more or less holding steady at their 2010 positions.

Those were the headline Westminster voting intentions. How did these correlate with constitutional attitudes? In total, YouGov found a majority against independence, with 30% supportive, 54% opposed, and 16% undecided.

As you can see, although levels of opposition to independence were high amongst Labour voters (70%) and Liberal Democrats (75%), the Conservative voters' opposition topped the chart, with a full 90% of them opposed to Scotland becoming independent. These figures do not tell the full story, however. They represent only the percentages of respondents sampled, rather than their prevalence in the wider Scottish electorate. There are, for example, far more Westminister Labour voters than any of the other groups. So what, if anything, about the national picture can we say on the basis of these findings?

For the sake of mischief, let's take the 2012 YouGov findings and the popular vote each party attracted in 2010, and combine them. Let's assume that the levels of support, opposition and indecision for each political party is the % YouGov identifies and that the electorate who turned out in 2010 turns out for the referendum in 2014. To make that a bit more concrete, the Tories received 412,855 votes nationally in 2010. Combined with the YouGov rates of opposition and support for independence, that'd tot up to 371,570 Tory votes agin independence, 28,900 in support, and 12,386 undecided.

There are problems with doing so which are worth bearing in mind. To sketch a couple, voting behaviour in constituencies are far more amenable to strategic calculation, and tactical voting, than an up-or-down referendum vote and we can't take account of that by generalising from election figures. Secondly, YouGov do not include those who intend to vote for "others" in its breakdown, so we're missing between 2.5 - 5% of voters here. In a close campaign, we can't afford to leave such folk out of our calculations, but the limits of the data here necessitates doing so. Thirdly, the Liberal Democrat collapse after the 2010 election has significantly altered Westminster voting intentions, and the likelihood that the party will receive just under 19% in the next election seems remote. That said, it seems less likely that the constitutional attitudes of formerly Liberal Democratic voters has evolved substantially in the same period.

For our purposes, however, these numbers need only really be indicative: what serious opportunities are there to persuade Scotland's Tory voters to back independence, and how many are there there to persuade? How many might we expect an explicitly anti-Conservative independence campaign to lose us from the get-go? The brief answer is, sod all. On YouGov's figures, the 16% of undecided voters might look something like this in terms of their voting intentions for Westminster.

In the same vein, if the electorate of 2010 turned out, and supported independence at the level of YouGov's sample then the (unsuccessful) 30% of the Yes electorate would look something like this:

And lastly, the triumphant No coalition might resemble something along these lines.

Brown envelope stuff, but it gestures towards the fact that a) the substantial majority of undecided voters support the SNP and Labour at Westminster and b) while the 20% separating Labour (70%) and Tory opposition to independence (90%) doesn't seem a lot, when you tot up what those numbers mean in terms of the electorate out there to be persuaded, there seems little to be lost from holding back on the anti-Tory rhetoric. That is not, of course, to say that the rhetoric will be devilishly effective, but that's a matter for another blog.

Just over 400,000 voters may support the Tories in Scotland, but on the evidence, only a tiny sliver of them are undecided, with the vast majority intractably opposed. They are the Conservative and Unionist party, after all. As we saw from their leadership elections in 2011, even the idea of more devolution still seems to stick in their craws like a butterless cream-cracker, and get the old birds wheezing. More interesting, in some respects, is the scale of the Labour electorate which this fag-packet calculation suggests might turn out for independence. Just as we tend to underestimate the levels of support still attracted by the Tory party in Scotland, the YouGov stats might suggest that something in the region of 207,000 Labour voters, in a bad poll, would vote Yes, however poorly represented this sensibility may be in the party's parliamentary rank and file.

Make no mistake. If voting intentions look like this in the autumn of 2014, YesScotland would get crushed. In the gambit to reach 51%, however, undecided, unpersuaded Labour and SNP voters look far riper prospects for the prospecting independence supporter, trying slowly to build up that stray 21%.